Last fall semester, I was able to take an independent study where I expanded my knowledge of SQL beyond its traditional use of querying relational databases for text and numeric values. Instead, I began using it as a standalone GIS, using it to store and query geometries (points, lines, and polygons).

One of the ways in which I initially learned to use PostGIS functions (my new RDMS of choice) was to redo some homework assignments from a previous introductory course in GIS- but using SQL functions instead of ArcMap geoprocessing tools. This particular homework assignment sought to illustrate a use case for buffering, dissolving, and intersecting. By transliterating the workflow from ArcMap into SQL code, I was able to create a process that was reproducible, easy to understand, and more efficient to run. Plus, there was no file bloat of intermediary files- a common data management problem when geoprocessing data in ArcGIS.

The assignment simulates a problem easy to envision occurring in the natural resources sector: “Forest management staff have asked you to develop information to assist with the application of pesticides… Management intends to apply pesticides to areas within 200 meters of each infested point.” The goals of the project include:

- Finding total area of each forest cover type within 200 meters of an infested point

- Finding out whether streams pass through the application areas

- Finding the length of each stream segment that passes through an application area, and what type of forest cover it passes through

*You can download the data for this tutorial on my github, here.

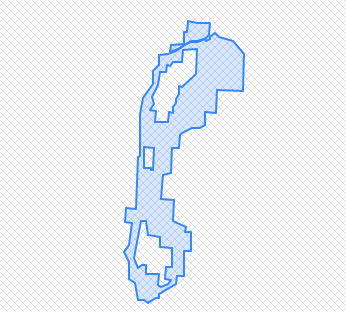

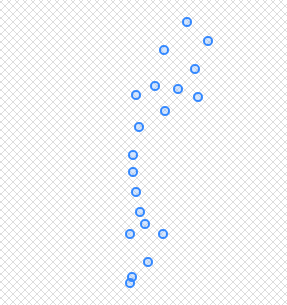

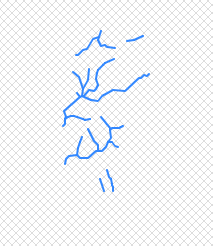

We are given 4 different set of geometries, stored as shapefiles:

- Park boundary (polygon)

- Infestation points (points)

- Streams (lines)

- Forest cover type (polygon)

First, I uploaded each shapefile into its own table in the database with a specified schema. I used ogr2ogr through the command prompt to accomplish this.

ogr2ogr -f "PostgreSQL" PG:"host=localhost user=postgres dbname=postgres password=******* port=5432" D:\FILE_PATH\boundary.shp -overwrite -lco precision=NO -lco GEOMETRY_NAME=geom -nln "staging.kemo_bound"

ogr2ogr -f "PostgreSQL" PG:"host=localhost user=postgres dbname=postgres password=******* port=5432" D:\FILE_PATH\infest_point.shp -overwrite -lco precision=NO -lco GEOMETRY_NAME=geom -nln "staging.kemo_infest_points"

ogr2ogr -f "PostgreSQL" PG:"host=localhost user=postgres dbname=postgres password=******* port=5432" D:\FILE_PATH\streams.shp -overwrite -lco precision=NO -lco GEOMETRY_NAME=geom -nln "staging.kemo_streams"

ogr2ogr -f "PostgreSQL" PG:"host=localhost user=postgres dbname=postgres password=******* port=5432" D:\FILE_PATH\vegetation.shp -overwrite -lco precision=NO -lco GEOMETRY_NAME=geom -nln "staging.kemo_vegetation"

*ogr2ogr comes with GDAL. Install that if you have not already.

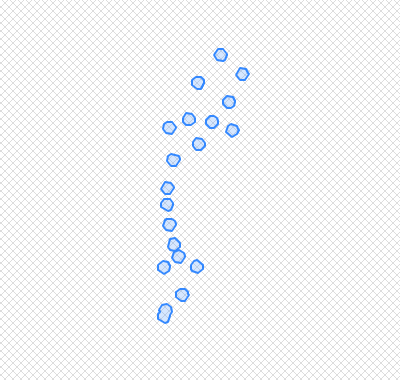

Let’s take a look at our inputs:

The first task was to create a buffer around the infestation points, and to dissolve the boundaries. You can do this in a couple ways. The first is the create a nested query, like so:

--create buffers and dissolve boundaries

select (st_dump(st_union(blah.st_buffer))).geom from

(select st_buffer(staging.kemo_infest_points.geom, 200)

from staging.kemo_infest_points) as blah

You can think of this method as querying the results of another query. Using nested queries when I first learned database management helped me understand more intuitively how databases functioned. Additionally, it was crucial for helping me to understand the WITH statement (also called a common table expression, or CTE), which is very important for making large queries easier to read and understand. Nested queries by themselves can often be messy, lack conciseness, and can become overly verbose. Though important to learn, it is often best to avoid using them if possible. A better method would be the following:

SELECT (st_dump(st_union(st_buffer(a.geom, 200)))).geom

from staging.kemo_infest_points as a;

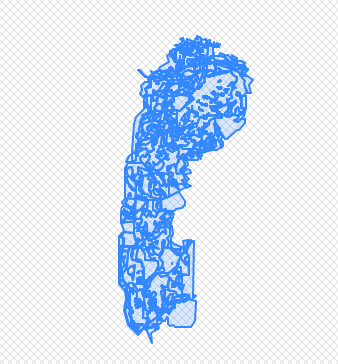

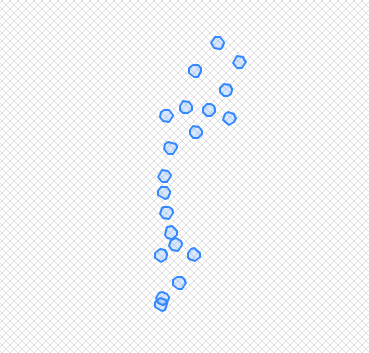

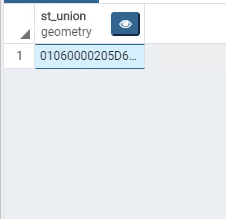

Both result in the same output. See below:

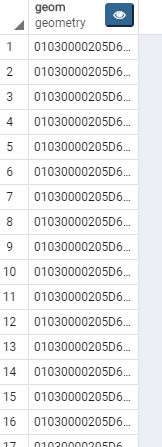

Let’s break down this process. First, we use the ST_Buffer function, on a.geom (with ‘a’ being the table, infest_points, as it has been given an alias), and give it a buffer of 200 meters. Geom is the column that holds the geometry of infest_points. Remember that we set this name originally in our ogr2ogr command. Using ST_Buffer alone (without the other functions) would produce the following result:

SELECT st_buffer(a.geom, 200)

from staging.kemo_infest_points as a;

As you can see, we still need a dissolve. Which leads us to adding the function, st_union().

SELECT st_union(st_buffer(a.geom, 200))

from staging.kemo_infest_points as a;

The problem with this, though, is that no longer maintain the individuality of each buffered point. Each buffer has now been merged into a single record, which is not what we want. To avoid this, we use ST_Dump(). According to the PostGIS documentation, ST_Dump can be thought of as the opposite of a GROUP BY clause. Remember to add .geom at the end of your select statement, otherwise you will be returned an improperly formatted column formatted geometry column without the desired visuals.

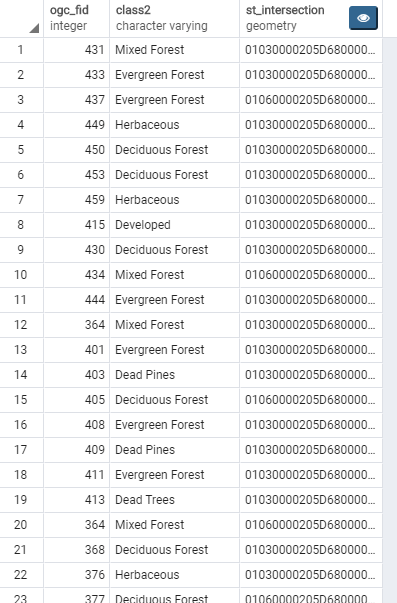

Knowing this general methodology, let’s skip ahead to my near-final product. You will now find that at this stage in my coding, I reverted back to nested loops! Not the most pleasant sight. It’s hard to believe, but this hard-to-read chunk identifies the forest cover within each buffered location, and those sections that are within the park boundary. But how does it work? What are those inner joins doing? Not easy to tell with the way this code is formatted…

select veg_intersect_t.ogc_fid, veg_intersect_t.class2, st_intersection(st_intersection, geom) from

(select ogc_fid, class2, st_intersection(dissolve_geom, geom) FROM --select FID, vegetation class, and only geometry that is within buffer zone

(SELECT dissolve.dissolve_geom, b.* FROM

(SELECT (st_dump(st_union(st_buffer(a.geom, 200)))).geom as dissolve_geom --buffer and dissolve points

FROM staging.kemo_infest_points as a) AS dissolve

INNER JOIN staging.kemo_vegetation as b ON st_intersects(dissolve.dissolve_geom, b.geom)) as joined) as veg_intersect_t

INNER JOIN staging.kemo_bound as c on st_intersects(veg_intersect_t.st_intersection, c.geom)

What I am about to show will start to make the above more readable. I will introduce the WITH statement, or CTE query, which as I mentioned previously provides an easier way to write large SQL queries. See the documentation for that here. This code chunk below is equivalent to the above, and a bit easier on the eyes:

WITH buffer as (select (st_dump(st_union(st_buffer(a.geom, 200)))).geom

from staging.kemo_infest_points as a),

vegetation_intersect as (select ogc_fid, class2, st_intersection(b.geom, buffer.geom)

from buffer

inner join staging.kemo_vegetation as b on st_intersects(b.geom, buffer.geom))

select vegetation_intersect.ogc_fid, vegetation_intersect.class2, st_intersection(vegetation_intersect.st_intersection, blah.geom) as good_geom

from vegetation_intersect

inner join staging.kemo_bound as blah on st_intersects(vegetation_intersect.st_intersection, blah.geom)

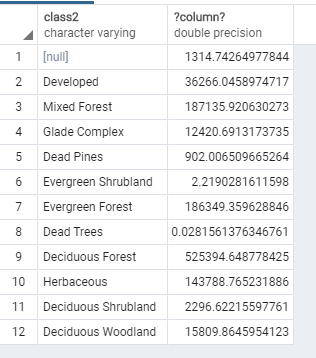

The WITH statement is akin to a nested query, but allows users to separate their code into chunks, piping one query into the next quite easily, even on an ad hoc basis. See how we can easily add an extra line at the end of the above code to return the area of each forest type that will be impacted by the pesticide application:

WITH buffer as (select (st_dump(st_union(st_buffer(a.geom, 200)))).geom

from staging.kemo_infest_points as a),

vegetation_intersect as (select ogc_fid, class2, st_intersection(b.geom, buffer.geom)

from buffer

inner join staging.kemo_vegetation as b on st_intersects(b.geom, buffer.geom)),

hygge as (select vegetation_intersect.ogc_fid, vegetation_intersect.class2, st_intersection(vegetation_intersect.st_intersection, blah.geom) as good_geom

from vegetation_intersect

inner join staging.kemo_bound as blah on st_intersects(vegetation_intersect.st_intersection, blah.geom)),

woohoo as (select *, st_area(hygge.good_geom) from hygge)

select class2, sum(st_area) * random()

from woohoo

group by class2

*Note that I added the random() function to the code just as an assurance that no future student will copy my results.

The WITH statement turns a convoluted chunk of code into something easily reproducible, and makes streamlining the workflow a relatively quick process. It is probably one of the most important concepts I have learned this past semester.

I may write a future blog to investigate in more detail how intersections using ST_Intersects and INNER JOIN work in PostGIS. That tutorial will also seek to answer those two remaining questions: Do any streams pass through the application areas? What is the length of each stream segment that passes through an application area?